my new favorite food book

my review of Rebecca May Johnson's SMALL FIRES; or, how a recipe for tomato sauce can contain an entire unending epic

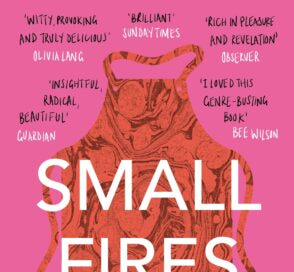

About a year ago I got my grubby hands on a galley for Rebecca May Johnson’s Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen1. I was lightly familiar with Johnson’s blog/newsletter, Dinner Document, where for the last decade-plus she has written in spare but inviting prose about what she eats and cooks; but that subtitle hooked me. The book arrived, bright pink and eager, and I tore through it.

Johnson’s book gave shape to so many half-thoughts and questions I’ve had in the kitchen for the past ten years. In it, she uses a Marcella Hazan tomato sauce (no, not that one) to investigate the literary potential of the recipe, and the kitchen as a site of praxis. She claims to have cooked the recipe a thousand times, a journey she calls a hot red epic. While we’re familiar with the food memoir in which a writer traces her life through meals, this is a memoir of a single recipe, shot through with criticism and theory and thrilling formal experimentation.

Last week I published a review of the book in n+1, and I’m quite proud of it. It’s a joy to be able to go long on a handful of topics you care so deeply about—for me, that includes 1. the recipe as a narrative/literary text, 2. home cooking as an intellectually rich practice, 3. home cooking as a practice with a fraught gendered history that I am compulsively drawn to and often annoyed by, 4. the recipe as a method of cultural transmission.

🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅 read my review here 🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅

One thing I love about the book is how grounded it is in the physical act of cooking: choosing a recipe, walking to the store, buying some droopy basil, coming home, putting on music, fastening an apron to your body, holding a knife in your hand, smelling the sizzle of garlic in oil, wincing at the hot splatter of oil on bare flesh, wishing to fulfill a friend’s cravings, shaking your ass to the music while the sauce cooks, maybe fucking the sauce up, eating it anyway, eating it happily, fork to mouth. Johnson’s primary argument here is that the recipe is deserving of critical and academic study/curiosity/thought, and that it has been ignored by critics and academics in part because they treat it like a theoretical idea rather than a living practice.

🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅 read my review here 🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅

One fun part of writing this piece was actually cooking the sauce in question—I figured Johnson’s book warranted this level of reciprocal praxis, of physical engagement, of being game for the terms she has set forth. I made the recipe twice, in part because there are two versions of it mentioned in Small Fires—the one published in Marcella’s Essentials, and one published by Ruth Rogers in The Guardian in 2006. The differences mainly come down to the quantity and preparation of the garlic; the recipe teaches Johnson—and us—how important those differences can be.

I have taken great joy in bastardizing the recipe over the last year, a process that Johnson would call the emergence of my voice. I have developed my own opinions about how I like to combine oil, garlic, and tomato, and what types, and in what sequence. This is how we learn, the book argues: by taking the text and making it our own, not through thought but through messy action. Often I will slice my garlic, because that way the pieces are big enough to avoid burning (most of the time) but small enough I don’t mind finding them laced through my pasta. I will cook it gently in oil, just until the slices’ edges get gilded. I will often add a squirt of tomato paste here, because of its depth, because I like stirring it in the pot and watching it go from tomato to brick red. If I have some good anchovies or even some mediocre anchovies I might add them too, because an anchovy always allures. Before I dump in a whole tin of tomatoes I will make sure I am not wearing a white or expensive shirt, and then I will splat the tomatoes into the pan, using my kitchen shears either before or after to slice them up, a pleasant efficiency. Thirty minutes is often a good amount of time to simmer a quick sauce like this, in part because you are unlikely to get bored or restless in 30 minutes. Forty-five or 50 can sometimes make your toes start to tap. I like to make a whole batch of sauce and then just as much pasta as I want for dinner, it’s a control thing, I’ll cook the pasta take out some pasta water drain the pasta and return it to the pot with the pasta water and some starting amount of sauce. Then as it all bubbles together maybe I’ll add some more. Certainly the Italian way is to serve pasta just smeared in tomato sauce, not swimming in it, but sometimes you’re just here for the sauce, the pasta is an excuse. (Imagine pappa al pomodoro made with this sauce!) A shower of Parm, if you want it, if you have it. Rogers called this recipe “the nicest thing there is”, and there are nights when I agree with her, and these are often nights when I’m feeling tired and unoriginal.

🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅 read my review here 🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅

I have just finished up my first ten-day residency in Vermont, just kicked off this low-residency MFA I’m doing at Bennington. I’ve been thinking a lot—sometimes too much!—about the book I’m writing, which has absolutely nothing to do with food. In other words, I’m setting out on this enormous project that has nothing to do with the thing I’ve been writing about for a decade, the topic I know the most about: cooking. I often worry about this disconnect, both from a craft perspective and, when I’m feeling particularly craven, a marketing perspective. What does it mean that I have spent a decade figuring out how to write about cooking, and now I might spend another decade figuring out how to tell the story of this crazy magic company I grew up in? Any through-line I come up with often feels invented. But since the review published I’ve been thinking again of a Natalia Ginzburg quote that Johnson cites in her book. I’ve been holding onto it like a life raft, like a promise. It proves, I think, the value that cooking can give us, even when we’re doing something totally other. Cooking is a way of thinking, after all, and learning to think is always a useful pursuit. The Ginzburg quote comes from an essay about her writing life. After explaining that, for a moment, she tried to write like a man, she says:

Now I no longer wanted to write like a man, because I had had children and I thought I knew a great many things about tomato sauce and even if I didn't put them into my story it helped my vocation that I knew them.

The great gift of Johnson’s book, for me, is the immense seriousness she attributes to the mundane, everyday act of home cooking. Do it or don’t do it, but put some respect on its name.

🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅 the review is right here 🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅

if you make a purchase through these links I may make an exceedingly small commission, fyi

https://twitter.com/Kyla_Lacey/status/1670903935404589057?s=20