From the Archives: Character Dining at Disney

An old Lucky Peach piece on magic, disney, childhood, and Pooh’s Breakfast Lasagna

Hello from vacation! Since I’m away this week I thought I might share something I wrote years ago that isn’t available online; it’s the one thing I’ve publicly written about the magic company I grew up in, which I’m now writing a book about. I’ve long wondered if there was a way to talk more in-depth about the book on Mess Hall, and this is the only answer I’ve found.

The piece appeared in Lucky Peach’s 2015 Fantasy Issue, and was the first thing I wrote for the (now-shuttered) magazine, a huge writing milestone for me. It’s about character dining at Disney World, something I grew up doing with select members of the magic company on our twice-yearly trips. It was also the first time I wrote about Cesareo, the director of the company and an influential and looming presence in my childhood.

Reading it now, I’m amazed by how anxious I still am about revealing certain feelings about an experience that mostly seemed sunny to outsiders. It’s a complicated history I’m still figuring out how to tell, but this was my first stab at it, and I’m grateful that I was in such good hands: the piece was edited by the brilliant Rachel Khong (hi Rachel!). I like to think my writing has improved since 2015, and I’m lucky that I’ve found a path towards telling this story that doesn’t solely focus on my perspective. But I’m also proud of this piece, which meant so much to me when it came out, and wanted to give it a permanent home here. I have ever so slightly edited it, but it is basically the same as it was 8 years ago.

At Disney World, restaurant reservations open 180 days in advance—a full six months before you sit down for your meal. Smart planners and experienced parents know this. In my last-minute scramble for character-dining reservations two weeks before my trip, the best I could do for a Saturday morning breakfast was an off-site meal at the newly constructed Four Seasons: Goofy & Pals Character Breakfast, party of one.

I take a seat on a squeaky black leather banquette inside the stark hotel restaurant and wait for my table. Mickey and Minnie are being ushered out of the dining room by hotel staffers, the characters waving their oversized, gloved hands, their handlers assuring us that Mickey and Minnie will “be right back!” The mice blow kisses and strut out the door.

A voice comes over the loudspeakers: “Good Morning, Everyone! It’s time to start the day off right—and there’s nothing like a good breakfast and good friends!” “Zippity Doo Dah” plays. People begin to clap along. “Stand up if you have something to celebrate! A birthday, a vacation, an anniversary, or if you’re just having a WONNNNDERFUL DAY! Now let’s wave our napkins around our heads!” Servers wave white napkins around their heads. Some of us follow suit. Some of us stand up. I don’t remember this particular song and dance; I keep my seat.

From roughly the ages of three to ten, I was spoiled by twice-yearly trips to Disney World. We never missed the character breakfasts—sometimes we would attend a couple in a single trip. In my memories, we sit at the center of a long table, with Mary Poppins and her friends milling about gaily, stopping by to chat and take photos, delighted by our presence. We are the special guests at their cheery brunch party, and the air is hazy and white, smacking of stardust.

*

Cesareo was the man who brought me to Disney World every year. I called him my godfather, which was a convenient untruth. I wasn’t baptized as a child, but “godfather” was easier than its more accurate and lengthy alternatives.

In the 1970s, Cesareo bought an old vaudeville theater in Beverly, Massachusetts with an eager group of young people. He was a psychology professor and the magnetic sort of teacher who accumulated students—including my parents—like a rolling ball of tape picking up lint. After a few months of cleaning up the theater’s layers of gunk and showing old movies that didn’t make any money, he announced that they would be making magic.

As a child in Havana, Cuba, Cesareo watched many traveling magic shows: men like Fu Manchu (actual name: David Bamberg) and The Amazing Chang (Samuel Lewis Whittington-Wickes), who styled their acts with an Asian aesthetic and played to packed houses across Latin America. These men would have a strong influence on Cesareo’s own spectacle: lots of kimonos and dragons, intricately painted boxes, technicolor curtains. By the time I came along, Cesareo and company had already performed at the White House seven times and been the subject of a feature in TIME magazine. They had done almost everything by hand: reupholstered the auditorium’s chairs, sewed dozens of curtains and costumes, built and painted illusions, and taught one another to sing or tap-dance or juggle. I was one of just a few children in the show, and I was raised a star.

Onstage I was Princess Marian, jumping out of boxes, twirling, expressing surprise while other people jumped out of boxes, tap-dancing, wearing sequined, ribboned costumes that my mother had helped sew. Sustaining a smile for two and a half hours every Sunday made my cheeks hurt.

The magic company was one big extended “family” that spent much of their time together in tights and stage makeup. I mostly resented it, after the ease and freedom of childhood morphed into the stubborn desire of puberty. I couldn’t leave on the weekends, I never got to go to sleepaway camp or join traveling soccer teams, and I could never understand why everyone did the bidding of this man who was so keen to lash out or cut them down. (He’d tell you, with great authority, that screaming at and publicly humiliating company members were teaching mechanisms.) But while Cesareo was often cruel and manipulative in his relationships with adults, he spoiled my older sibling and me. We were his shimmering stars and he made it known loudly and often. I got to eat all the candy I ever wanted. Twice a year we went to Disney World.

Cesareo saw Disney World as an important place to bring girls and boys who were still young enough to appreciate magic. On our stage, I knew how everything worked, all the secrets, the trap doors and hidden pockets and diversion tactics. I knew the secrets behind my levitating in a toy car and my mother’s getting sawed in half, and feigned shock and awe when ducks appeared from previously empty boxes. I was well versed in falsehood. But I still believed in Disney.

*

Character dining offers park visitors the opportunity to do two very important things: eat a meal, and interact with characters without waiting in line. The food is an “all-you-care-to-eat” buffet. And an extra five dollars buys you insurance: the staff makes sure that every character in the room visits your table, and will periodically check in, casually making conversation about whether or not you've seen Mickey yet. Sometimes they explicitly tell you that they can “go grab him if you need me to,” like that guy at the club who can definitely get you into the VIP area.

The characters take pictures with you, sign your autograph book, and talk to you like you’re the most special person in the world, like you’re already old friends, like you could talk for hours if they didn’t have to scoot off to the next table to make that family feel special, too. As a kid, these meals were the crowning glory of every trip. I have no recollection of the food.

As a grown-up, I notice there is a prescribed route that each character takes through the dining room to ensure a visit to each table. I see her handlers, invisible to the younger me. It is all a very well choreographed and expertly performed dance. I know that there are human adults behind masks and fake eyelashes, and that last night’s Ariel wasn’t the same girl as today’s. When the young girl at the table across from mine gets up for a second helping of Mickey Mouse–shaped mini waffles, her doll falls face down on the banquette. In the girl’s absence, Minnie Mouse walks over, rights the doll, and pats it on the head, playing steward to that little girl’s fantasy even though she’s stepped away.

I fill my first plate of buffet food, which at the Four Seasons is slightly better than the average hotel buffet: the eggs aren’t leathery, the pastries resemble pastries, and I have the option to put Nutella on my toast or add “superfoods” to my granola. As I eat, I worry about what I’ll say to Minnie.

She approaches my table and I wave, assuming nonverbal communication is a safe bet. She waves back exuberantly. Her plastic mouth is stretched into a static smile, her eyes forever open, perpetually excited, on the verge of a blink. I say, “Hi, Minnie!” and she hugs me and kisses me on the cheek. I say something very stupid, like, “Oh, that’s nice!” and she does not appear to judge me for it. We take a photo together and wave goodbye.

*

I'm not sure why we stopped going to Disney World. Maybe I lost interest, maybe the trips—which I’ve been told were considered company expenses—became too pricey. Cesareo and David bought a condo elsewhere in Florida, which offered a new vacation trajectory. When I was fourteen, I left for boarding school, happily shedding the burden of weekly performances.

On visits home, meals with Cesareo became an obligation. We’d either go to the Joe's American Bar and Grill attached to our nearest mall, or one of the local restaurants where fish tanks were central to the décor and Cesareo always ordered the baked haddock. He'd ask me how school was going, the requisite inquiries. A few times he asked about my sex life, and then offered to let me get married at the theater, as if he were doing me a favor. He'd make a rude comment about the waitress and wink at me. Under all those sequins, I slowly learned, lay an ordinary misogynist.

My senior year of high school, he collapsed outside the theater, had a stroke. Soon he was eating from a wheelchair, his speech warped by a drooping cheek. Food slipped out of his mouth and conversations with him turned into fragments. I was twenty-four and out of the country when he died. I have to read my old journals to remember how sad it made me; it’s too easy to picture him as an angry old man. There is no glow around my memories of him, only pockets of light from days in Florida, those earliest and warmest glimmers.

It’s been seventeen years since I’ve been to the Magic Kingdom, and as I begin to get my bearings, small fragments of the landscape trigger flashbacks: glimpses of memory, but never a full scene.

Main Street, USA still leads to Cinderella’s castle. The road is so full of people that it feels like we’re at a very well organized, very peaceful protest. The street is still lined with shops and ice cream parlors, but there’s a new Starbucks concealed by an awning that reads Main Street Bakery. The shops are flush with product; I assume that every time an item is taken from a shelf, another one immediately takes its place. On the far corner, just across from Cinderella's castle, there’s another bakery that you can smell even before its awning comes into sight. This is thanks to a machine called the Smellitizer, which pumps fresh cookie smell—no actual cookies involved—onto the streets to comfort and lure passersby. Everything is extremely clean. (If any Disney employee sees a piece of trash on the ground, they are required to pick it up. Characters, with their bulky costumes and appearances to maintain, are exempt.) I begin to remember a certain giddiness. It’s like muscle memory. I’m tempted to skip down the street.

I spend my afternoon weaving through the park, surprised by my sense of wonder and how it’s managed to endure. I can’t remember the last time something made me as giddy as the stomach-spinning plunge of Splash Mountain. I ride on Dumbo, which I remember as my must-ride-it-seven-times favorite. (It is a very basic ride for small children in which you sit inside a painted circus elephant—Dumbo—attached to a rotating central pole and use a joystick to move yourself up and down through the air.) I’m not expecting much, but then it is exhilarating. I cackle and scream. They could cast me for a TV advertisement. I look out over the park. I am flying.

Gliding through the sky, whizzing through the burnt sienna of Thunder Mountain, watching royalty walk down the street, I remember this feeling. Disney has never competed with other theme parks on the height or the speed of its roller coasters—it leaves that record setting to Six Flags. Instead, it wins with the completeness of its experience, its total dedication to magic and hospitality.

The characters are central to this success. As I learn from a former Disney princess, Characters are divided into two types: Fur characters whose faces are covered by their costume and who never speak—Mickey, Goofy, Donald Duck, Daisy, et al—and face characters, whose faces you can see, and who will eagerly talk to you. Everyone starts out as the former.

The audition process is extremely competitive, particularly for face characters. You can only audition once each year; you do so in front of a panel of four or five people, who will role-play different types of park visitors. “They make it feel like you're in Hollywood,” a former Jasmine (and before that, Mickey) told me. “When you get the part, they always phrase it like, ‘We want to offer you the role of....’ They want you to really feel like you’re a part of this amazing production.”

Character training includes learning to walk around as your prescribed character and—very importantly—how to sign your name. Consistency is essential to the fantasy: all of the bubbly Poohs must look the same in autograph books, all instances of Minnie Mouse must have hearts instead of dots over the i’s. The signature must look the same at Disney parks in Tokyo and Orlando. Face characters watch the movie from whence they came before undergoing training on how to speak and act. Princesses are taught how to apply their makeup just so. At Meet and Greets, guests wait in lines that can stretch as long as ninety minutes to meet high-demand characters like Elsa from Frozen. There is always a handler nearby with his or her eye on the clock. Characters are never out for more than twenty minutes. It gets hot under those costumes and tiaras can dig into one’s scalp. Smiling nonstop gets exhausting.

Every cast member (staff working on the park grounds are all called cast members, even if they aren’t performers) is trained never to point with one finger. If a guest asks for the location of a bathroom or It’s A Small World, you gesture with your index and middle finger, the rest of your fingers folded into your palm. It’s less aggressive, less harsh, and reminiscent of air traffic controllers.

*

You get to Epcot Center from the Magic Kingdom via a quick ride on Disney's public transportation system, the Monorail. “Epcot” is an acronym for “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow,” and its most recognizable feature is Spaceship Earth, a geodesic sphere that houses a time machine, among other attractions. Behind it lies the World Showcase, where eleven pavilions, each representing a different country, ring around a lake. Every pavilion has its own menu and themed merchandise shops.

I remember Cesareo taking us to the Morocco pavilion, where waiters in embroidered vests poured hot tea from awe-inspiring heights. Once the tea cups were in front of us, Cesareo would take a lump of sugar carefully in his spoon and dip it repeatedly in the liquid, as if basting it in tea. The way they stir in sugar in America is too noisy, he’d say—and clank around his spoon wildly, threatening to shatter the colorful glass. This is how we did it in Cuba. He loved to show us all the ways that he was right.

The World Showcase uses real countries to further the Disney fantasy, but there are still characters to be found. You’ll often see Jasmine and Aladdin canoodling in Morocco. At dinnertime, the rest of the Princesses can be found in Norway.

After enjoying a sunset glass of Prosecco in Italy (Epcot is special because, unlike the rest of the park, you can drink alcohol here), I walk over to Norway and get in line. The number one Character Dining destination is at Cinderella’s Royal Table in the Magic Kingdom—it’s the toughest reservation in all of Disney, and often sells out the day that reservations open. Akershus Dining Hall in Norway comes in a close second. A cast member steps out from the restaurant and calls my name, and when I walk up and wave, she looks behind me expecting a younger sister, maybe, or a patient boyfriend. “Oh—just you!” she says, quick to smile, and ushers me inside. On the other side of the door I fall behind two girls, seven or eight years old, and quickly realize the purpose of our line. Around the corner, I see a big yellow hoop skirt, and wavy brown hair. It’s Belle, the princess who loves books and a velvet-clad Beast. She asks me about my day; I get nervous and hold up my disposable camera, sheepishly: Could we take a photo? As she signs my autograph book, Belle holds her smile as though there are clothespins attached to her dimples, then waves goodbye.

A hostess dressed in Norwegian attire leads me to a table in the middle of the room. All around me are families and small children. Each table includes at least one young girl under the age of ten. Roughly half are dressed as princesses, but all of us are addressed as such. (“Hello, Princess!” is the refrain I hear most frequently over the course of the weekend.)

My server must be roughly my age, smiley and actually from Norway. She seems more excited to be here than I am, nearly bursting with anticipation for me as she explains the sequence of my meal: a buffet for the first course, then entrée, and dessert, and each princess will come say hello at some point. She tells me how much she loves Disney, so much that sometimes she comes here alone too. She encourages me to order the frozen vodka drink named after her hometown. I order it and it tastes like a daiquiri made with vodka, slushy and cloying. It hurts my temples but I tell myself this will enhance my experience, like taking MDMA at a concert with a light show.

I help myself to the first-course buffet, which runs the gamut from baby carrots and squeaky dinner rolls to smoked herring and gjetost, that soft, caramel-y Norwegian cheese. Back at the table, I see the princesses enter the room, as if released from gates. They begin to make their rounds, floating along a path they know by heart.

Princesses move in a very specific way, with intention and grace and always a smile. Their posture is impeccable and they seem never to accelerate or decelerate but rather glide along at a programmed speed, hands either lifting up flexed wrists and lightly bent elbows (the “I’m about to twirl or sing” stance) or holding up a very large skirt (the “I’m rushing off to find my prince and/or sing” stance). Everything they encounter is a delight. “Well, hello!” and “Oh, my!” are common exclamations. Conversationally, they do the work for you. They ask earnest, specific questions. They would be great on a first date. Given the limited amount of time each one spends at my table—ninety seconds, max—our conversations are surprisingly detailed. Snow White and I discuss the gooseberry pies that she likes to make. Ask a princess how she’s doing, and she won’t just tell you that she’s splendid but also why: Aurora, the Sleeping Beauty, is having a good day because she’s awake and hasn’t seen any evil spinning wheels she might prick her finger on. Ariel mostly talks about Eric (her One True Love) and asks me if I have a prince (I don’t). They are the nimblest improvisational actresses I’ve ever watched.

Cinderella, that blue beacon of majesty and grace, approaches and notices that I am a party of one, a very rare unicorn in this land of family fun. “Oh, you’re dining alone tonight! I tried to do that, but the mice joined me. They just wanted to eat my cheese.” She leaves my table beaming, as if we’ve both acquired a new best friend. Despite my blushing, my aloneness, my insecurity, I feel special and taken care of. I imagine it’s what Cesareo wanted me to experience here. In his absence, it’s simpler.

The meal progresses swiftly. My server whisks away my buffet plate and someone presents me with a butternut squash raviolo drowned in cream sauce and geometrically drizzled with a balsamic reduction. A manager drops by to check on me, and asks about my pasta. “It’s seasonal!” she exclaims. “We’re so sad to see it go!” Even her lamentation is cheery.

Desserts are plated for a crowd at Akershus, so I get three: chocolate mousse cake, a sweetly gummy apple cake, and some sort of rice cream topped with raspberry coulis, the consummate dessert garnish of the nineties. I would have enjoyed them more back then, would have eaten the whole plate if given the chance, and then torn around Epcot in a manic sugar rage. Tonight I take a few bites and wait politely for my server-friend.

“Now it’s time for me to get your autograph,” she explains, delighted by her turn of phrase, and hands me my check. She lingers, eager for more conversation. I assume she doesn’t get many guests my age to talk to. “Are you heading back to the Magic Kingdom for Wishes?” she asks, eyes sparkling.

At ten p.m. every night, Cinderella’s castle lights up in blue, and a fairy godmother tells us about stars and their power to make wishes come true. On that first “wish,” a single firework bursts from right to left across the sky over the castle, and a young girl’s voice comes over the speakers singing “Star light, star bright,” followed by an entire chorus singing “When You Wish Upon A Star,” that ur-text of Disney’s core belief system.

It is a fireworks show with a narrative arc, a symphony of bursting sparkles. Mickey’s voice assures us that the most fantastic, magical things can happen, and it all starts with a wish. Tinkerbell’s likeness flies over the crowds. We hear the personal wishes of Princesses and Pinocchio and Peter Pan. I cannot help the swell of feelings and hope that builds in my chest like a cheery sort of anxiety. It is a uniquely Disney tingle.

My mother says that we saw these fireworks often, that we all loved them, but no matter how many times I close my eyes and try to remember, I can't find the image or the feeling. When we talk, she can sense my wariness, can predict the cloud that Cesareo casts over these memories. She is well aware of my resentment. You've got to understand, Marian, that those trips were for you. We all got to go and be a part of it, but those trips were for you to have a wonderful time. You just loved it.

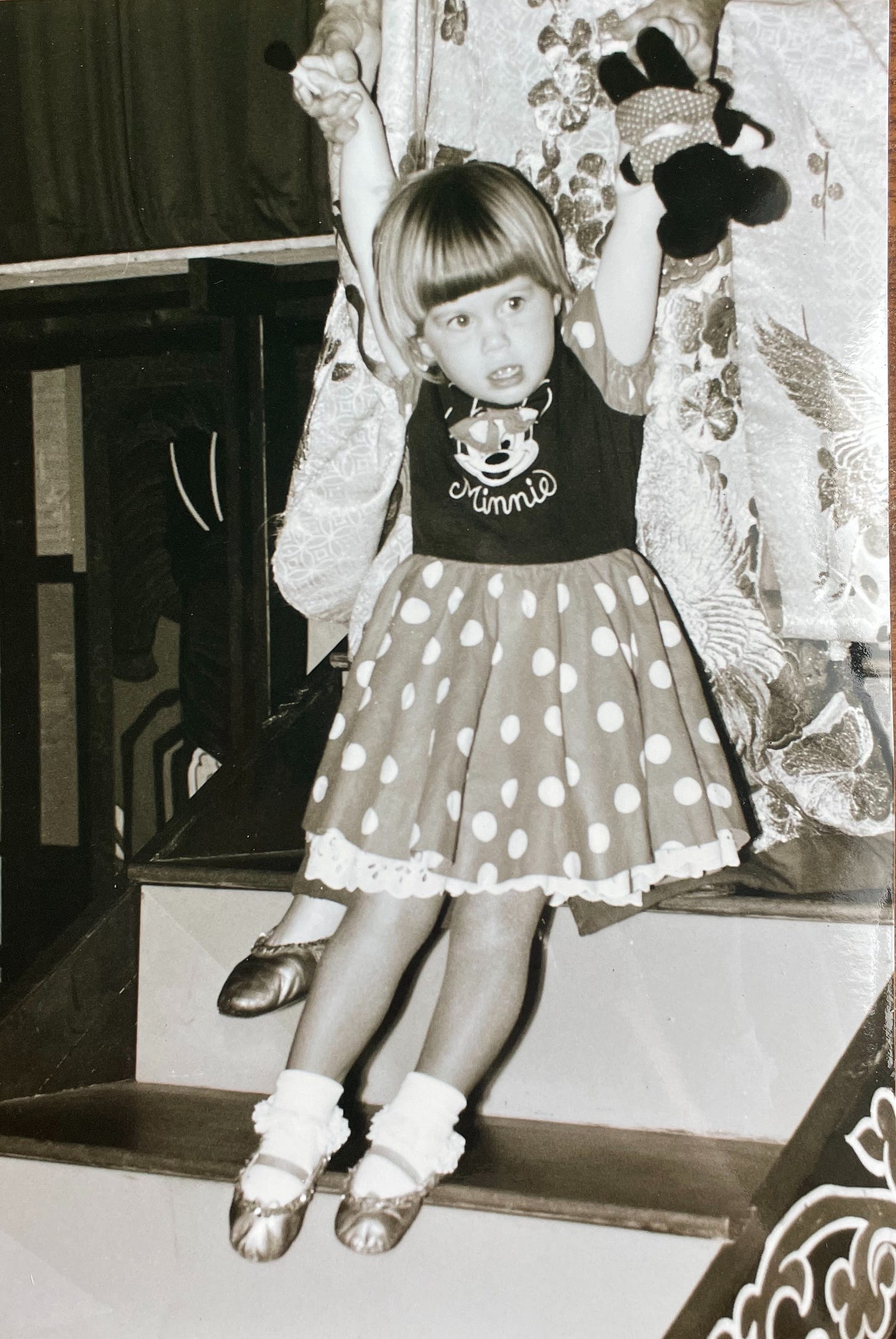

Somewhere in my parents’ house, there’s a photo of me with Jasmine and Aladdin; I've seen it hundreds of times. We had somehow gotten into the park early; they were setting up for a parade. My mother doesn't remember all the details, but she says we ran into the happy couple, they thought we were VIPs, and immediately treated us as such. In the photo, you can see my face struggling to contain my smile.

The night’s great success is not a wish or a thousand wishes coming true, but rather the infection of wonder. All the small things that create the sort of spectacle that leaves our mouths agape and our eyes blinking towards the sky: they aggregate to Disney’s inimitable, benevolent power. Somewhere along the line, a spell is broken, and I realize I’ve managed to lose Cesareo’s stubborn ghost—or at least banish it from the park.

*

Sunday brings another character breakfast, this one more smartly chosen, at the Crystal Palace, in the heart of the Magic Kingdom.

As with any breakfast buffet worth its flat fee, the restaurant’s interior is thick with energy, the clanking of silverware, the friendly hum of conversation that hasn’t yet been soured by two-hour lines, the glee of children tearing into Mickey-shaped pancakes. I sit down at a two-top near the kitchen entrance and watch a cast member gently escort Winnie the Pooh from table to table, ensuring his girth doesn’t knock over an unsuspecting tyke.

By this time I am a character-dining expert, and have loosened up enough to enjoy myself without too much self-consciousness. When Pooh approaches, I take a cue from the Princesses, and act like I’m greeting an old friend. The human inside the bear and I both know the dance we’re supposed to do: he sees me and opens his arms wide, then presses his paws to his cheeks in surprise (It’s you!). I wave and force my mouth agape, testing the limits of where my cheeks can go (Hello!). I stand up, awkwardly scooting out from my banquette, and we hug. I ask for an autograph and then a photo. His handler steps in to wedge my pen into a fuzzy bear paw. I hand my camera to the handler, then swing my arm as far as it can go around Pooh’s back.

After Pooh, and before Piglet or Eeyore, the father at the next table strikes up a conversation. He’s here with his wife and a daughter only a few years younger than me, and I learn that they are all lifers—they’ve been coming to their timeshare since their daughter was a tiny princess-worshipper. They don’t do character dining much since it’s so expensive—only once a year or so. This used to be a “regular” restaurant, he explains, “until they realized they could charge twice as much with some characters.” When those characters approach, his daughter greets them with a sincerity that I’ve been trying to muster all weekend.

I study her as I poke at my serving of Pooh’s Breakfast Lasagna, a casserole of pancakes, waffles, pound cake, pastry cream, custard, bananas, and sticky strawberry sauce. I take a bite and feel electrocuted with sugar. The ceiling of the Crystal Palace is a grid of windows, old and thick, that filters the morning light into something hazy and white, just as I remember it.

Dear Marian,

This is one of the best papier I read in a while. Your Friday newsletter is the sweet which ends my week, i love it, i'm fascinated, almost addicted. And this piece, wowwwwww. Read it on the train, it was a perfect moment.

Thank you.

Great read. The behind-the-scenes details are fascinating. Off to google that breakfast lasagna...