Welcome back to Mess Hall, the internet’s most sublime cooking newsletter. The following began as a “recommendation” post for paid subscribers only, but it turned into something I felt excited about and wanted to share with a larger audience.

Please consider supporting my work by signing up for a paid subscription, which is just $5 a month, or $40 a year.

Last week I sat in a New Orleans backyard overflowing with plants—a loquat tree, pink yellow purple flowers reaching out from various crannies, a leggy fig, encroaching weeds, a jasmine bush obscuring my view of the outdoor shower—and spoke to Jackson on the phone. He was excited to spend a few days here, eager to leave New York and be somewhere he’s never seen or smelled. We’d gone to Miami for a quick weekend in January, but it was freezing cold (50 degrees and windy, poor things), and he still hadn’t regained his full sense of smell since getting Covid in December. He’d step outside, eager to huff the scent of a new city, and instead receive a grey nothing. Surrounded by plants and sea air and unable to suck any of it up—a tiny hell. As a result he was a bit depressed and I, ever the loving girlfriend, was growing weary of the daily comforting. I kept promising that it would come back, and I meant it!, but neither of us knew yet that it would.

Are things blooming down there? He asked me on the phone as I sat and looked out at the ecstatic fecundity in front of me. I laughed big: blooming was an understatement. The profusion of growth and flower and leaf here makes me feel like an interloper—not just in a city I don’t know very well, but in an environment where I, possessing no stamen pistil pollen or bark, often feel like the odd man out.

I’m here house- and dog-sitting for a friend, which means requisite twice-daily walks through the neighborhood. Unless Sid insists on walking down the busy truck-route avenue where he’s more likely to snag a scrap of food while I’m not looking, our morning and evening walks loop through quiet residential streets. Here the trees are flowering, the gardenias are flowering, the bottle brushes have spiked out wild and magenta. The star jasmine, though, puts them all to shame. It explodes and proliferates, announcing itself by the snoutful before you turn the corner and lay eyes on it. It covers whole fences: dense but gentle, its flowers tiny and everywhere, little stars of scent begging you to press yourself into their bounty. Makes perfect sense that jasmine has historically been used as an aphrodisiac and a calmative. I walk by half a dozen bushes each morning and ask them with a little wink, are things blooming down here?

I’ve never liked floral tastes—I’m sorry to all the delicate rosewater sweets out there but the flavor makes my mouth scream soap. It’s the rare flavor I just can’t abide, and actively avoid. All the more surprising, then, that I’ve latched onto a jasmine tea that was languishing in my kitchen for a year before I packed it into my New Orleans-bound suitcase, more an act of thrift than anything else. For my birthday last year, Jackson got me two elegant boxes of tea: one jasmine, one black. The black went quickly, but the jasmine I never touched; green tea isn’t a part of my general rotation, and tea is a thing of habit. Since giving up coffee because it made my anxiety go kookoo, I’ve insisted on an indulgent cup of tea each morning, heavy handed with the oat milk and local honey. Maybe it’s the whitewashed 90s health food connotations—a cup of green tea has rarely ever felt indulgent to me.

But I had a little tin of it shaking around my tea shelf, and I’m too obsessed with using things up, so I tucked it into my suitcase. We’ve had a chilly spring in New York, but here it’s gearing up to 90 as I write this. A hot morning beverage begins to lose its appeal. Instead I started brewing a big pot of tea in the afternoons to drink cold in the morning. This kitchen has a large Pyrex measuring cup with a lid that has a few straining holes—a smart accessory I’ve never seen before. So I’ll drop in a spoonful or two of tea leaves, fill the thing up with boiling water, let it steep for three minutes, strain it out into a big mason jar. I’ll steep the leaves twice, to double my yield: add more water, steep again, strain again. I add plenty of honey while the tea is still hot—it lends sweetness, yes, but also a bit of body to the iced tea, which helps ward off asceticism. I let the jug of tea cool while I go do something, then stick it in the fridge overnight. According to the tea experts, it’s more delicious to cold-brew your tea; Max Falkowitz claims that my boil-and-chill method results in “bitter mulch water.” And okay, I’ll try his method when I get back to New York, where I’ll have a fresh order of tea waiting for me at home. But I’m a philistine—I love my mulch water. And I don’t find it bitter: It is grassy and floral all at once, revivifying, perfect.

I’d performed this ritual twice before realizing that the little white wisps in my tea came from the same plant I’d been smashing my face into every day on the side of the road. Of course. Like the tea was preparing me for my audience with the real thing. It often takes me a while to put two and two together. “I tend to think of plants as either landscaping or food,” writes Kate Lebo in last year’s The Book of Difficult Fruit, “and don’t notice them until they’re labeled for me, after which they appear everywhere.” The book is an encyclopedic essay collection that celebrates and investigates the darker side of fruit, the magickal and remedial histories of the wild bushes that go unnoticed on the side of the road. Reading it has helped me remove some of the mental barriers I hold between myself and the natural world, barriers that living in New York City can too easily fortify.

Jasmine, then, has come to define my trip. My first day here I wrote the word PLEASURE on a periwinkle post-it and smacked it down on the desk next to my computer like a talisman, mantra, reminder, insistence. Yes I am hoping to write here and read here, to begin to do something with the work I did in Massachusetts this winter. But I was worried that I’d be too focused on production and not enough on absorption, so I resolved to prioritize pleasure over most things. The flowers help, the tea helps. (Plus I sleep a lot.) If I were a different sort of person I’d consider, or even encourage you to consider, drying jasmine flowers at home, and then mixing them into loose tea. But outsourcing is a primo luxury. I make enough work for myself in the kitchen, and nothing I try my own hand at will be as fine as Grace Tea’s Flowery Jasmine Before the Rain. I’ve considered making simple syrup, but worry it would break the tea’s spell, would change the connotation of the flavor. I fear giving the flower a second job in my culinary life. Also, I do not want to drink perfume. Somehow the brazen sultriness of the live blooming jasmine turns subtle when dried and mixed into tea, floral in a gentler, more rounded way, not cloying and never soapy. It makes for the most beautiful morning, I don’t know how else to put it.

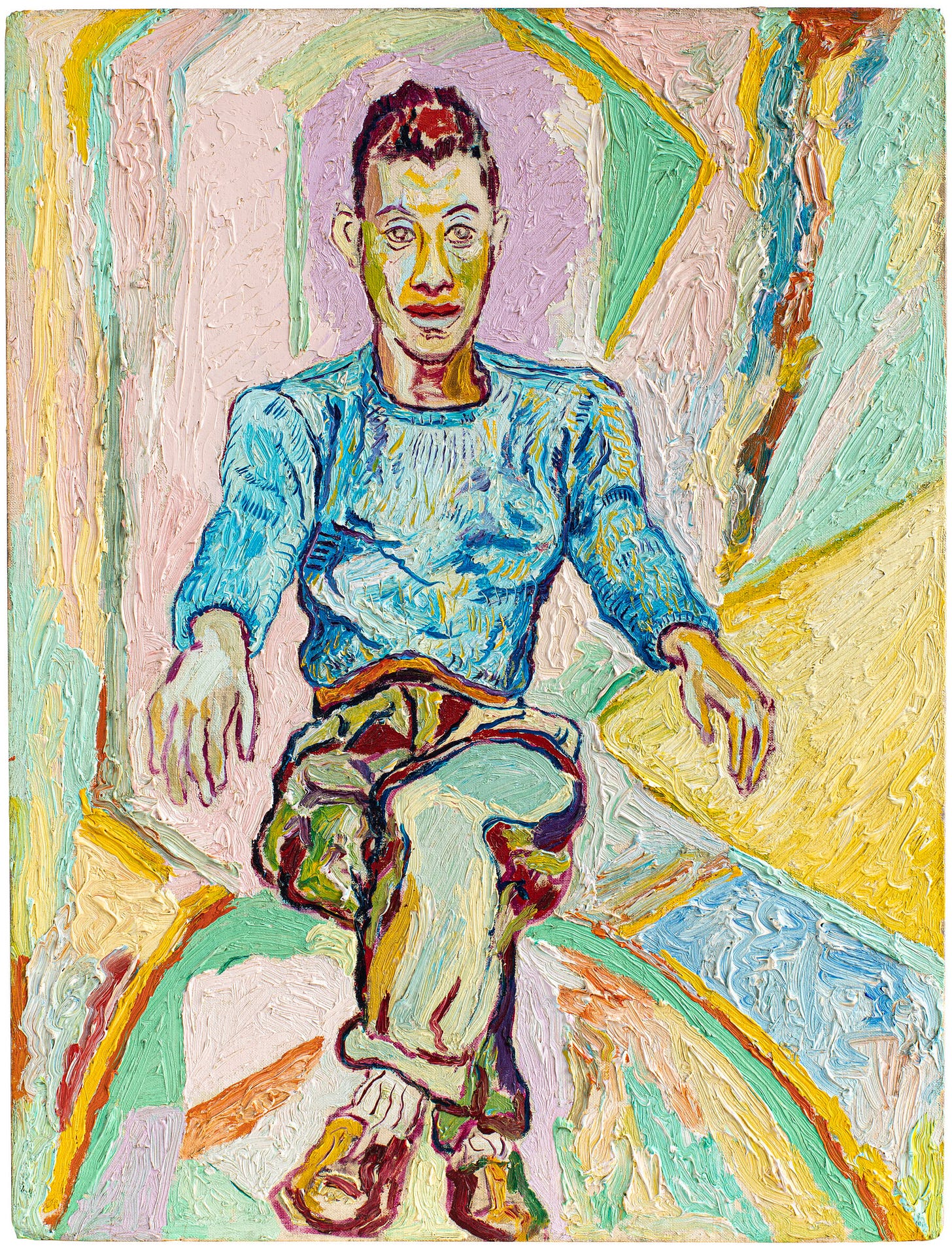

On Sunday I went to the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, in part because there was a painting I needed to see. Bo Bartlett’s Young Life had hung in the entryway on my last visit there in 2016, and had stuck in my craw. Something about the composition, the big blue sky, the dark underbelly of Americana, of masculinity too. The way the girlfriend clutches the boy-man’s stomach has always felt unsettling to me. Most importantly, though, it lured me towards an exhibit of Beauford Delaney’s paintings.

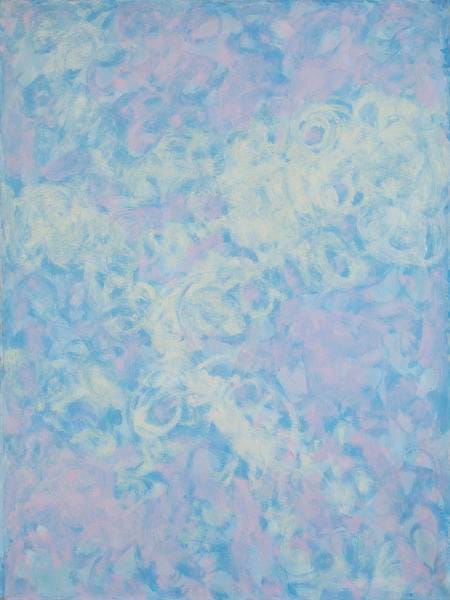

One of my countless intellectual insecurities comes from my difficulty with abstraction. Blame a too-pragmatic brain, but I’ve often struggled to connect to abstract work as deeply as I’d like to. Delaney’s brushstrokes cracked that open for me like a spell. The exhibit, called Be Your Wonderful Self, intersperses a handful of abstract works into an impressive collection of his portraits, in order to show the ways that the former informed the latter. I loved it all, but the abstract paintings took me over. I began to understand: the paintings are dancing, you dummy. I suppose it’s more accurate to say that Delaney impasto-wrangled his paint until the light danced through it. The paintings absorb you, your whole face, like a jasmine bush. The light wiggle-bounces like the wind makes the flowers do. Delaney was a devotee of Monet, and you can see the water lilies through his eyes, refracted through the dazzle of his surfaces. Flowers, like paintings, as vessels for light.

Delaney was born in Knoxville, TN, in 19011, one of ten children in a Black Methodist family. By 1929, he was living in New York, splitting his time between Harlem and Greenwich Village and painting mostly street scenes and portraits. He became a close friend and confidant of James Baldwin, whose portrait was maybe my favorite of the bunch—I’m a sucker for wobbly lines and fauvist colors. Baldwin, the story goes, encouraged Delaney to move to Paris, where he could live less encumbered by the racism and homophobia of his home country. (Unless I missed something, the Ogden seems afraid to explicitly call Delaney gay, and instead just vaguely references “sexuality.” ??) Paris was where his abstract work appeared and fully realized itself, in part thanks to the time he was able to spend with Manet’s canvases. As this New York Magazine piece tells it, that move also alienated Delaney in new ways: he couldn’t speak French; he wasn’t in New York during a pivotal moment in the New York art world. He rarely returned home, and died in a psychiatric hospital in Paris, broke and alone. (If anyone would like to buy me a copy of David Leeming’s very expensive out of print biography of Delaney, please be my guest.)

And of course I couldn’t stop thinking, while walking the gallery, what would it be like to live a life where I could just focus on the important work?2 To cast off the work I do because it pays well and can be performed efficiently. What would it be like? Sure, in Delaney’s case, that scenario meant living penniless, isolated in various ways, largely unknown, still now underappreciated. It’s a thought spiral easy to nosedive into when confronted by the lives and work of artists, especially those who were able to eke out a working life in some of the world’s great cities before real estate interests made them unlivable for the majority of artists. Read Ninth Street Women, and you’ll want to scream, both because this (difficult!) life was actually possible back then, and because all you want to do after reading it is dedicate yourself to the big work.

For me, spending time away from New York always means an existential crisis over whether moving somewhere else—say, New Orleans—would allow me the freedom to cast off the work I don’t care about. I usually forget this panic once I’m back in New York, but maybe someday I won’t. The problem is I like my friends too much to leave them. (Delaney painted his from memory.) And still, I wrote and underlined in my journal: I crave the luxury of focus. Here is a different sort of pleasure: allowing your brain to luxuriate on one idea, one project, one goal, rather than a constant switching between tasks. The latter can quickly kneecap creative work.

Down a floor from the Beauford exhibit was a small alcove of works from Dave Greber, a digital artist who has described his work as “intuitive tech folk-art.” The first work I saw looked like a game of Candy Crush rebooted in an elfish web 1.0, a projection of gems tumbling down through a pothole, the projected area decorated with glittery butterflies and scraps of paper. Stranger still was another video, called The Casebearer 2.0, a constantly mutating, semiabstract moving digital collage. I’ll let the museum text explain the rest: “Artificial Intelligence generated narrators tell the mystic poem of a plaster bagworm moth’s life cycle as the insect transverses the ceiling of the artist’s studio. The creature is a metaphor for self-sufficiency and grace in the face of precarity as the narrative diverges into an alien nature documentary or self-help video.”

The sweetest way to discover art is to fall into it the way those gems fell into the pothole: an inadvertent tumble that turns out luminous. Somehow Delaney’s abstraction had prepared me for Greber’s bizarro sublime. A couplet from the bagworm poem has been tumbling through my head all week, a grounding merciful robot reminder:

I don’t want comfort

I want God

I’m sure it will delight a few of you to hear that his father’s name was Samuel Delaney

If you would like to help me answer this question, please consider a paid subscription to this newsletter :)