Kristen Miglore on Exploding the Recipe + Simplifying the Granola

A conversation with the cookbook author on what a recipe should be, and what makes something GENIUS. Plus a recipe for life-changing granola.

When I was a baby editor at Food52 the greatest possible thrill I could imagine was a mention in Kristen Miglore’s weekly Genius Recipes column. Kristen—who hired me as an intern and nurtured me as a writer—has been writing the column now for 11 years, unearthing recipes that change us as cooks and elegantly outlining what makes them tick. Her columns speak of the frustrations and joys of the home cook, the pleasures of eating, and the lineage of each dish, including how she found it, or who referred her to it. This was the first bit of writing that showed me a recipe could not just include a narrative, but be a narrative in its own right. Hitting control F and successfully searching for my name in one of these columns was a weird sort of honor: maybe the first time was the Parker + Otis pimento cheese? Becoming a “genius tipster” meant that I was, in a way, learning to read recipes and think about cooking as meticulously and expansively as Kristen did; I was honing my taste, developing my own list of questions I was asking in the kitchen. So many genius recipes shaped the way I cooked, and became cornerstones in my kitchen; ten years ago, Hurricane Sandy hit three weeks after I moved to New York to work with Kristen, and I cooked a big pot of Broccoli Cooked Forever and baked Nigella’s Dense Chocolate Loaf Cake for Shay and Tom as they hunkered in my Greenpoint apartment for the weekend.

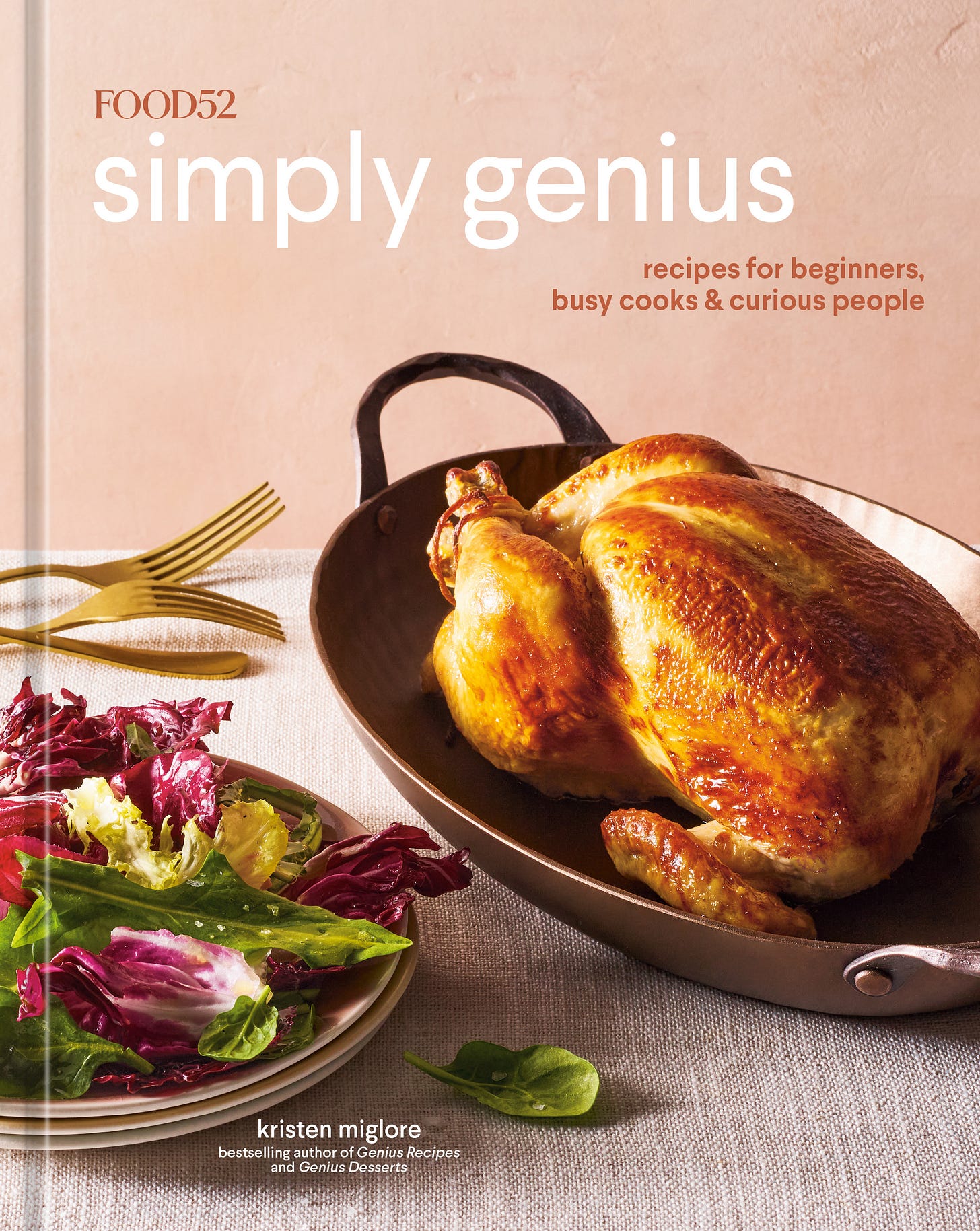

The thrill of acknowledgement remained last month as I flipped to the back of Kristen’s new book, Simply Genius; I believe I qualify as a tipster for tuning her on to Molly Yeh’s Roasted Potatoes with Paprika Mayo. This latest book is something of a departure from the first two Genius books (Genius Recipes and Genius Desserts, respectively). Recipes include ample riffs, pairing suggestions (food, not wine), and occasionally advice on what to do if you fuck up; an entire page coaches you through the often-discussed frustrations of making pancakes that are rarely baked into a written recipe. The book is joyful and occasionally zany—I am still freaked out by the avocado-banana tartine, but I’ll follow K until my taste buds’ death—with a tricked-out design geared towards answering the questions that cookbooks often omit. Kristen understands that the bounds of a recipe are often larger than we give them credit for, which is why she has gone so far as to detail exactly how she does the dishes at the back of the book.

Obviously I wanted to get my old boss and forever mentor-slash-friend on the horn to talk about the book and recipes in general, and I had so much fun getting into the weeds with her. Order a copy of her book here, and scroll down for a brilliant granola recipe that I’m eager to fold into my kitchen life.

Marian: I really want to try that chocolate oatmeal1.

Kristen: I keep talking about that oatmeal because it is the one that we make all the time—[my daughter] Mari asks for it.

It really does solve this problem that is unique to home cooking: oatmeal makes a mess. The pan is not a problem of the recipe itself, but it’s this problem that exists within the life cycle of cooking the dish.

Yeah. And it does really speak to what I was trying to do with the book, which is to not leave anything out—for better or worse.

I realized as I was [writing the book] that there's really only so much more you can add to a recipe before it becomes unusable. You can try to think of every possible question that someone could have, or every possible hiccup they could run into. But that's how I accidentally took Andy Ward and Jenny Rosenstrach’s recipe for for pork shoulder ragù and turned something like a 150-word recipe into a 3,000-word recipe. I tested out what happens if I take their very simple recipe and filled in every possible gap I could think of. And then I had to dial it back and say, okay, when this actually gets on the page, do we really need to explain to people how to unwrap their pork shoulder and pat it dry, in so many literal ways? I had to make some compromises with that kind of stuff. I had to figure out, what are the things that are going to be genuinely useful, and what are the things that are helpful, but just adding bulk?

So that thing with the oatmeal is one of those details that does not usually get included in a normal cookbook. A breakfast chapter isn’t gonna tell you how to clean your pan. But it is something that, practically speaking as home cooks, we run into a lot, and it's the kind of thing that we feel really smart when we figure out a solution to. In this case, Sam had told me how she always made oatmeal in a non-stick skillet for her three-year-old at the time. And so that piqued my interest, and I came back to her and asked her for a recipe.

When you said the thing about feeling smart, I thought, that’s an interesting definition of a genius recipe. It has an aspect to it that makes you feel smart when you’re doing it. How has your understanding of what a genius recipe is changed since you started the column in 2011? I think the banana toast, for example, is so different on a conceptual level from the Marcella sauce.

One way they’ve had to evolve with this book especially is that I’ve had to look for the things that really do fit into a busy life and really are streamlined. I had the luxury in the early days of mostly focusing on techniques. I think a lot of them were fairly practical, because they had garnered an icon status over time as recipes that would be passed around by people. So inherently they had to fit to people's lives. With the Marcella sauce, the results are so surprising and unexpected and delicious that you wanna keep making it, but also it fits into your life easily because you're not doing a lot of prep work. So that had all of the elements that make a genius recipe: something surprising, something that makes you feel smart, that makes you want to brag to your friends about it and try to indoctrinate them into making a recipe a certain way, because it'll improve their life. We want to keep it in our lives forever.

But I did feature more complicated recipes [in the early years]. It didn't matter if it took a long time, as long as it had something interesting to say and the results were worth it. And I still want to have a place for those recipes in the column. But the reality was in my own life, the recipes that I was looking for are the ones that are simpler and simpler and simpler.

And I think that there's also this idea of, you can take the oatmeal recipe once and then you're constantly iterating on it. Whereas something more complex—I’m thinking about the Ignacio Mattos fava beans—I’m glad that I know about it, but I’m probably never going to make that recipe.

Right. And with the granolas, the Nekisia Davis granola is forever going to be so many people’s favorite. So many people have made it and added their own riffs. I make it for gifts when I don’t know what to get people. But there's also the granola in this book that completely shocked me in so many good ways. I was recovering from Covid when [I first wrote about it]. I was taking care of Mari—I was starting to get better, so I was able to give [my husband] Mike a break. It was my first time making the granola and I was like, okay, this is something we can do together, and I need to test the recipe. And we made it completely together and she never wandered off and we were eating it and the kitchen was clean 15 minutes later.

The other granola—which I love and definitely has a place—takes like 40 minutes at least, even more if you wanna get it crispier, and you stir every ten minutes. Which is fine, but when you have a 20-month-old making it with you, opening the oven every 10 minutes is a bigger ask than it used to be. When life has squeezed out all the free space, these are the recipes that still fit for me.

I want to hear about how the book changed since its inception—I mean, you were working on it for five years, right?

Mmm-hmm. We sold it as a book called Genius Cooking, though we never really thought that title would stay, or knew what that title meant. But the point was that it was gonna be a beginner cookbook. And we were going to try to answer all the questions that recipes leave out—for good reason—out of necessity. You can't put everything on a page. But I was still creative director of the whole brand and we were still like doing all these infographics and fun visual experiments in the studio. And so we were trying to bring a lot of that extra visual handholding to a cookbook.

Those elements are still there, but over four years of working on it, I realized that it was not just a beginner cookbook, because I needed the recipes so much myself. And we also realized how tricky it is to include all of that stuff. That's part of why it took four years, because we were kind of breaking apart and putting back together what our cookbook pages could look like and that's really, really hard to do. And one of the things that I feel really proud about, looking back, is working really closely with our designer, Lindsey Allen, iterating and iterating on these things.

I’m always thinking about how food writers can actually teach people how to cook. And I’m so curious how you approach that task.

If we had the time, I would have asked Mike to cook the entire book. Because he cooks way less than I do, and doesn’t really use recipes when he does. I think it would’ve been really, really informative. I think the way that I made up for that was experiencing 12 years of questions on Food52—some of them specifically with these recipes. Some of it went into the “Common woes” pages. [Which include] not just how to fix it next time, but what to do with what’s in front of you if it’s too tough or too spicy or whatever. Is that answering what you’re getting at?

I think you're giving an incredibly pragmatic answer. You're understanding what the problems are and trying to solve them.

Yeah. And when I was first learning to cook, I didn't think I wanted to use recipes because it sounded boring and it sounded uncreative. But obviously all I've done in my career is champion recipes. And I think recipes are how I learned to cook. I mean, even in culinary school they gave us recipes and they had teachers pacing around us while we were following the recipes to point out when we were doing something wrong.

I learned to cook on my own, in the very beginning, with Julia Child’s The Way to Cook when I got my first apartment in college. I was like, I’m gonna learn to cook. And I sat down with this huge cookbook like, I’m gonna braise carrots tonight. That’s how I taught myself.

And one night I made these really delicious garlicky peanut noodles for myself without any recipe. And then I tried to make them again for Mike when we were first dating and they were inedible—I put too much garlic powder in them. So those kinds of experiences taught me to respect recipes as a starting point.

So maybe that's not a comment on how people learn to cook, but it's how I learned to cook. And I feel like I'm still constantly learning to cook from following other people's recipes and analyzing what makes them tick. And then when I'm staring at my fridge and thinking, Okay, what can I do with this broccoli, I go back in my mental Rolodex of tricks, and assemble from there. And that's really my favorite kind of cooking.

You've talked a little bit about what makes a genius recipe, and I'm curious—are there any books that you think are genius?

Oh my gosh. It's so hard because I always have to be moving on to the next cookbook. I don't always get to go deeper into a cookbook and keep cooking more and more recipes out of it, because I wanna feature as many different people as possible [in the column]. But especially after going through four years of trying to do new things with book design, I can appreciate it so much more when authors make a bold choice and it works really well.

Obviously, Ali Slagle’s book—I know it’s been a bit controversial because some people want all of the measurements for the ingredients in the ingredient list. And she made this brave choice to put it in the instructions. I loved it. Sometimes those ingredient lists can get so cumbersome when there's so much extra detail that has to be crammed in. Weight, measurement, volume, peeled and chopped, half inch. Sometimes it’s a paragraph for a single ingredient. And in her book it's so welcoming because it's just like the five or six things that you need to buy at the grocery store, and then you still can peek at the recipe and see, okay, I need a cup of this.

Similarly, Eric Kim's book, he's done this kind of perfect dance between the emotional memoir writing and very appealing, cookable recipes. Which is hard to pull off. Yasmin Khan does that really beautifully too, tackling subjects that are not easy to tackle in a cookbook space—balancing memoir, geopolitical history, and practical recipe writing and tips really, really beautifully.

Yeah—you’re sort of at war with an existing format.

Yeah. And I could go on and on, there's so many more. But all of these examples are people who are doing something new within an existing format. And I can't say enough how much easier it is to work with an existing template.

Are there books that you do feel like you return to a lot?

My reference books are the ones that I always turn to. Those are the ones that I keep on the shelves, in my office right by my desk. Those are the ones that when I'm wondering why something works, I dig through and can usually find an answer.

And I always come back to The Taste of Country Cooking by Edna Lewis. Her voice is very peaceful and calming, and the lifestyle she’s describing is very idyllic. And I stumble on new genius recipes from that book every time I look through for a different reason. When I went back for Genius Desserts, I found a tip for, when you have extra pie dough scraps, just tucking them into your pie or your cobbler so that they become little dumplings. And then for this book I think I have two recipes from that book. The skillet scallions, and her salad of Grand Rapids lettuce leaves.

The salad doesn’t have oil, right?

Yeah. I tried to picture what a salad with just vinegar and no oil would taste like, and I didn't really want to, but I trusted her and I had a good feeling about it. And it’s great. There’s a little bit of sugar in the vinegar to help soften it. There’s scallion, that adds some softness and dimension. And without the oil, it means that it can sit for an hour without wilting. It's so great to be able to question those assumptions—that you have to have fat in dressings, and you really don't.

Okay, my last question for you, which I've been asking everyone, which is all three people that I've talked to for this series—can you tell me what's in your freezer?

So many bananas [laughs]. Whole overripe bananas—I don’t take the time to cut them up or peel them. They look terrifying in the freezer and they probably take up too much space, but that means that when I wanna make banana bread—I did this with Mari last night—I can just put them in a bowl of warm water and the peels protect them and they defrost fast, for mashing into banana bread. So I have six fewer bananas in the freezer today than I did yesterday, but still too many.

++

Tahini Pistachio Granola

from Jenné Claiborne

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mess Hall to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.